USDA’s Failure to Enforce the Animal Welfare Act

Every presidential administration since George H.W. Bush in 1992 has featured a USDA Office of Inspector General audit slamming the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS)’s enforcement of the Animal Welfare Act. The most recent OIG audit, in February 2025, found that 80 percent of dog breeder inspections reviewed were noncompliant and blamed APHIS for inadequate procedures that enabled animal suffering.

The AWA is not an anti-cruelty statute but instead a federal administrative law governing commerce in animals. The USDA refers to the entities it is supposed to regulate as its “customers.”

Over the past ten years, Eric has written extensively about various aspects of APHIS’s failures regarding AWA enforcement, from analyses of inspection citations to stipulated penalties to trends in enforcement actions to lack of transparency to the use of damning case studies. Media such as National Geographic, the Washington Post, Science magazine, Nature, Reuters, and others have shed much-needed light on APHIS’s failures, including not acting in a timely manner—or at all—despite egregious and ongoing animal suffering.

Below are some examples of damning media coverage regarding inspections, penalties, and systemic failures; lack of transparency; and case studies such as Envigo, Moulton Chinchilla, SeaWorld, dog breeder Daniel Gingerich, and others.

USDA’s Staffing Problems, Weak Penalties, Cratering Inspection Citations, Catering to Business Interests, and Coddling Research

Employees terrified of being laid off. Shrinking resources combined with unprecedented workloads. The loss of a tool critical to enforcing its mission. Such conditions would strain any organization. But for an already overburdened division of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) responsible for overseeing the welfare of nearly 800,000 lab animals, they could spell disaster.

In the past several years, the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) has lost more than one-third of its inspectors, witnessed a doubling in the number of entities it has to oversee, and added an entirely new class of animal to its purview. . . .

“It’s the most challenging time I’ve ever seen for animal care,” says Kevin Shea, a former APHIS administrator who spent more than 4 decades at the agency before retiring in January. If APHIS can’t do its job, he says, “animals will suffer.". . .

Things became more difficult from 2018 to ’24, as the number of entities APHIS had to inspect doubled from less than 8000 to more than 17,000—driven largely by a rise in Uber-like services that move animals from, say, breeders to private parties. That same year, USDA lost a lawsuit brought by animal advocacy groups that compelled it to add birds—long excluded from the Animal Welfare Act—to its oversight duties. (Rats and mice are exempt from the act.) The agency must now oversee more than 63,000 research birds, more than dogs and cats combined. “It was a seismic shift,” says a current APHIS manager who asked to remain anonymous because they were not authorized to speak to the press.

At the same time, APHIS’s workforce is shrinking. In the first few months of this year, the agency lost about a dozen of its inspectors—approximately 15% of its oversight workforce—because of the Trump administration’s forced retirements and deferred resignations. It currently only has 77 inspectors—“a ridiculously small number for the job we have to do,” the APHIS manager says. “We’ve given our inspectors an impossible task.” The agency is under a hiring freeze, the source notes, so if more inspectors leave, they can’t be replaced. In May, the Congressional Research Service warned that “recent efforts to reduce USDA staff may further affect APHIS’s ability to carry out its oversight functions.”. . .

The agency was already under fire for alleged lax enforcement. Audits by USDA’s Office of the Inspector General over the years have chastised APHIS for failing to punish violations of the Animal Welfare Act and for not properly investigating repeat offenders. In a recent, high-profile case, the agency faced scathing criticism for taking no action against Envigo—a leading supplier of beagles for biomedical research—despite the documented suffering of thousands of animals at one of its breeding facilities.

“APHIS’s current challenges are a recipe for disaster for any agency, even one with the best record of enforcement,” says Eric Kleiman, a senior policy adviser at the American Anti-Vivisection Society, an animal rights group. “What we’re seeing now is a turbocharging of trends we’ve been seeing for decades.”

In light of these challenges, Kleiman is concerned APHIS will seek to outsource its responsibilities to third-party organizations. A 2021 Science investigation revealed the agency had begun an apparently clandestine policy of conducting more limited inspections of labs accredited by AAALAC International, a private organization of veterinarians and scientists.

Shea thinks “it’s inevitable” that APHIS will turn more to AAALAC. “If you’re trying to protect as many animals as you can, you have to rely on something beyond your 77 inspectors.”

That troubles Kleiman, who recently worked with another animal rights group, Rise for Animals, on an analysis of more than 14,000 USDA inspection reports between 2014 and the middle of this year. They found that although AAALAC-accredited research facilities account for just 42% of all inspected facilities, they received 73% of the two most serious types of USDA citations in that time period, as well as 78% of all fines issued by APHIS from late 2019 to mid-2024. Kleiman also slams AAALAC for giving a clean bill of health to facilities with a history of animal welfare concerns—including Envigo.

AAALAC did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Naomi Charalambakis, director of communications and science policy at Americans for Medical Progress, a biomedical research advocacy group, argues that the Rise for Animals analysis exaggerates the appearance of severe infractions at AAALAC-accredited entities by counting less serious violations in the total and by focusing on percentages instead of raw numbers. “Labs also often self-report issues to APHIS that they have already corrected,” she notes, “yet these issues still show up as citations.” Charalambakis acknowledges that AAALAC accreditation is “not a magic guarantee that nothing will ever go wrong,” but she says the analysis “paints a misleading picture of how animal research oversight works in practice.”. . .

APHIS can’t do that without sufficient resources, however, the APHIS manager says. “We can’t protect these animals if we can’t enforce the Animal Welfare Act,” they say. “Congress wants us to do more. But they don’t understand how little we have left in our toolbox.”

Research animals are already at a disadvantage under the Animal Welfare Act, and critics have insisted for decades that the act is insufficient and poorly enforced. . . . When a researcher violates the Animal Welfare Act, the USDA has few options for enforcement. Because inspectors cannot confiscate animals that are required for research, they can really only levy monetary fines. But for facilities that receive millions in funding and spend billions on research, fines—most of which are less than $15,000—are so low that they’re considered a “cost of doing business,” according to a 2014 USDA Office of Inspector General report. The USDA calculates these fines using an internal penalty worksheet, which factors in a facility’s size, compliance history, and the severity of its violations. The worksheet was recently obtained by Eric Kleiman, founder of research accountability group Chimps to Chinchillas, and it revealed that the USDA does not take a research institution’s revenue or assets into account when calculating fines. The USDA instead measures a facility’s size via the number of animals it uses, according to the worksheet, which divides research facilities into four size categories, the largest being facilities with 3,500 or more animals. But this metric is flawed, Kleiman says, since many labs don’t keep their animals on-site, instead contracting out with research organizations that perform the experiments on their behalf.

Toothless and ‘paltry’: Critics slam USDA’s fines for animals welfare violations

-National Geographic

Eric Kleiman, a researcher at the Animal Welfare Institute, criticizes the USDA’s fining system. With such “pathetic fines,” he says, facilities like these “can act with impunity, with resulting animal suffering, because they know [the USDA] will not act with any force.” Such small fines fly “under the radar” of public scrutiny and reflect the toothlessness of USDA enforcement, he says. . . . The USDA “coddles research, Kleiman says. The fines issued to Colorado State, Lovelace Biomedical, and the former Toxikon lab “are all paltry amounts for so many reasons, including but not limited to the severity of the citations—all involving animal deaths—the deep pockets of these wealthy research facilities, and the history. . . .at all three,” he says. Kleiman’s criticism echoes a 2005 report by the OIG calling for higher fines for research facilities violating the Animal Welfare Act. It pointed out that the amounts don’t vary according to whether the offender is “a small farmer that breeds dogs” or “a research facility with billions in assets,” making penalties for larger facilities “negligible.” . . . The USDA needs to rethink its process for issuing fines, Kleiman says— though he believes the entire agency, which he says “has failed to adequately enforce the law for decades, needs to be overhauled. “I can’t tell you how sick and tired I and other animal protection advocates are of opining, once again, about yet another [USDA] enforcement failure,” Kleiman says. “Thirty years of OIG reports, Congressional scrutiny, public pressure, media [exposure] and yet, what really changes?”

USDA accused of ignoring animal welfare violations in favor of business interests

-National Geographic

“How do you replace that kind of institutional knowledge and memory?” Eric Kleiman, a researcher at the Animal Welfare Institute, in Washington, D.C., says of the resignations of USDA animal care workers since 2017. When new inspectors replace those who have left, “all that they know is plunging enforcement, right? They have nothing to compare it to.” . . . Kleiman, of the Animal Welfare Institute, says he’s hopeful that after three years of not confiscating any animals, the agency is once again seizing those it deems to be in danger. But “praising the USDA for resuming confiscations is like praising an NBA player for knowing how to dribble,” he says. . . . For example, Moulton Chinchilla Ranch in Minnesota, which had its license revoked on October 8, has been cited for more than a hundred animal welfare violations dating back to 2013, including filthy cages, leaving the body of a newborn chinchilla to decompose, and accumulated feces. Yet for years, the USDA had failed to act, Kleiman says. In another case, the USDA inspected two facilities of Iowa dog breeder Daniel Gingerich an unprecedented eight times in July 2021, and inspectors documented more than 70 pages of Animal Welfare Act violations, but never seized any dogs. After he read their official reports, Kleiman says, the facilities can only be described as a “hellscape.” According to the reports, dogs were panting and gasping in the intense summer heat, several had empty or nearly empty water bowls, their coats were heavily matted, and many had skin conditions or oozing lesions. At least three dogs were found dead in two July inspections. “How that doesn't trigger an immediate confiscation is beyond me,” Kleiman says. “This is criminal cruelty.”

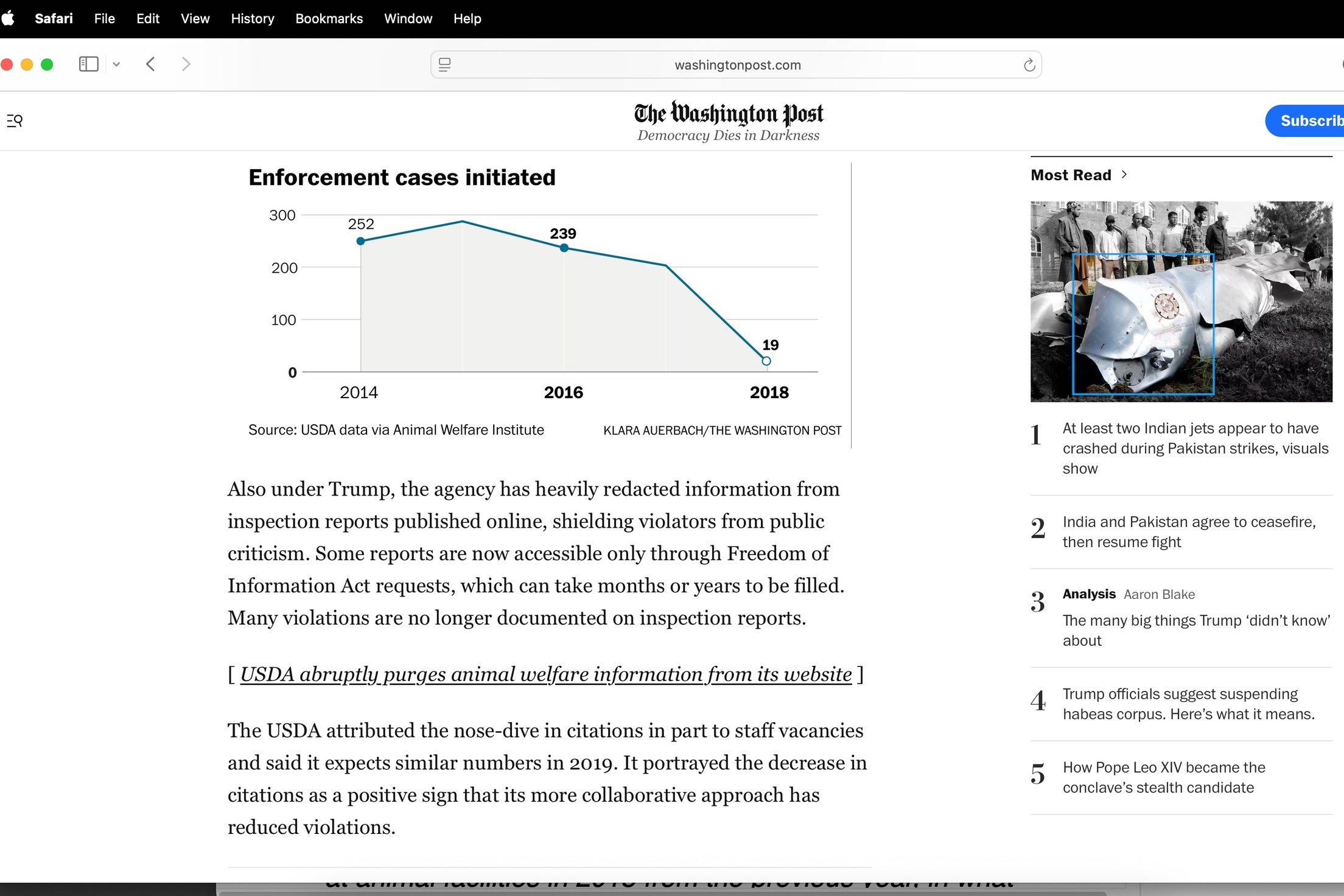

USDA inspectors documented 60 percent fewer violations at animal facilities in 2018 from the previous year, in what animal protection groups say is the latest sign of weakened enforcement by an agency charged with ensuring pet breeders, research labs, zoos and other exhibitors follow federal animal welfare laws. . . . In 2017, inspectors recorded more than 4,000 citations, including 331 marked as critical or direct, according to the Animal Welfare Institute, an advocacy group that tallied the figures using inspection reports published on a USDA website. In 2018, the number of citations fell below 1,800, of which 128 were critical or direct. The drop in citations is one illustration of a shift — or what critics call a gutting — in USDA’s oversight of animal industries covered by the Animal Welfare Act. Citations can lead to enforcement actions, including hearings and penalties, and those also plummeted in 2018.

USDA’s enforcement of animal welfare laws plummeted in 2018, agency figures show

-The Washington Post

Two years ago, the Agriculture Department issued 192 written warnings to breeders, exhibitors and research labs that allegedly violated animal welfare laws, and the agency filed official complaints against 23, according to agency data.This year, those figures plummeted: The department had issued 39 warnings in the first three quarters of fiscal 2018, and it filed and simultaneously settled one complaint — with a $2,000 fine or an infamous Iowa dog breeder who had already been out of business for five years….“It’s all part of this pro-industry, anti regulatory agenda,” said Eric Kleiman, a researcher who has tracked the USDA’s animal care enforcement for the Animal Welfare Institute, an advocacy organization. “We’ve never seen this kind of attack on the fundamental tenets of the most basic precepts of a law that has enjoyed long-standing bipartisan and public support for over 50 years.” . . . . “The thing that’s pernicious about the drop in administrative complaints is that those are the ones that have the most deterrent value,” Kleiman said. “Those are the ones where USDA is trying to send a message not only to the respondent of the complaint, but to the general regulated community. To have this kind of drop says to the regulated community, we’re kind of on your side.”

Law enforcement officials investigating Elon Musk’s Neuralink Corp over its animal trial program are also scrutinizing the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s oversight of the company's operations, after the agency failed to act on violations at other research organizations, according to several people familiar with the matter. . . . These sources said the decision by federal investigators to scrutinize the USDA was bolstered by criticism from the USDA's Office of the Inspector General, which has for years described the agency as overstretched and ineffective. . . . Only about 0.008% of the agency’s most recent budget of $430 billion goes to enforcing the Animal Welfare Act, according to Eric Kleiman, a researcher at the Animal Welfare Institute, an advocacy group. The figures were confirmed by Reuters “This funding is a pittance, as you can see, compared to the wealth, size and power of, say, many research facilities, let alone Elon Musk,” Kleiman said.

Concerns arise over USDA’s handling of SeaWorld Orlando -National Geographic

On December 13, according to USDA records, SeaWorld provided some, but not all, of the requested records. Nonetheless, based on the December 8 passed inspection, the USDA reissued SeaWorld Orlando’s animal exhibitor license on December 21….On January 26, the USDA cited SeaWorld for “fail[ing] to issue the records in a reasonable time. Then, in March, the agency issued the facility an official warning of an alleged violation for failing to furnish the information requested back in December. . . . Failing to hand over records is both a serious and rare offense for animal exhibitors, says Eric Kleiman, a researcher at the nonprofit Animal Welfare Institute—especially since the USDA classified this breach as “critical,” which can mean the violation had “a serious or severe adverse effect on the health and well-being of the animal,” according to the USDA’s inspection guide. Of the more than 45,000 inspections the USDA has performed since 2014, only a few dozen facilities have been cited for failing to hand over records, and only about five have received a critical citation for this issue. . . . In recent years, former USDA inspectors and staff have said the agency has demonstrated a pattern of neglect in its effort to prioritize business interests over animal welfare. In 2022, the USDA allowed thousands of beagles to suffer in poor conditions for months at a research breeding facility without reinspecting, confiscating any animals, or revoking the facility’s license. And fines for animal welfare violations are often so paltry, violators consider them “a cost of doing business, according to numerous reports.

Case Studies of USDA’s Failure to Enforce the AWA

Envigo—A USDA Disaster that will Live in Infamy

Envigo’s beagle breeding facility in Virginia was the worst enforcement failure in the history of the AWA. APHIS’s refusal to act was so appalling, so beyond the pale, so catastrophic, that a federal grand jury launched an investigation of APHIS’s actions—or more precisely, inactions—regarding Envigo.

Hundreds of beagles died at facility before government took action

-National Geographic

These violations and dozens more were documented in recent United States Department of Agriculture public inspection reports. Yet for months, the USDA, which is responsible for enforcing the Animal Welfare Act, neither confiscated any dogs nor suspended or revoked the license of the animal-breeding facility in Cumberland, Virginia. The facility is owned by Envigo, a privately held company with 20 locations across North America and Europe that provides animals for pharmaceutical and biomedical research. . . . Envigo’s record is an “unmitigated, unprecedented disaster,” says Eric Kleiman, a researcher at the Animal Welfare Institute, a nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C.. . . . Not attempting to establish why the dogs died violates the Animal Welfare Act. At the time of the USDA’s July and October 2021 inspections, Envigo had only one staff veterinarian to attend to 5,000 dogs. The USDA’s numerous veterinary care citations are “evidence that [one veterinarian] is an insufficient number,” Kleiman says. . . . The multiple severe violations documented at Envigo’s facility and the alleged failure to follow euthanasia procedures at Inotiv should be a wakeup call for the USDA to ramp up its oversight and enforcement of animal breeding and research companies, Kleiman says. “Research won’t police itself.” Kleiman says the USDA should send an unequivocal message that “no matter how large, how powerful, how wealthy” these companies are, animal suffering won’t be tolerated.

The contract research organization Inotiv is neglecting animals at a research facility in Indiana that conducts toxicity testing of experimental drugs, the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) alleged last month. . . . ”We believe that the HSUS investigation raises significant questions about animal welfare and good laboratory practice at Inotiv,” says Eric Kleiman, a researcher at the Animal Welfare Institute, an animal advocacy group. “Both the USDA and FDA should investigate.”

A major breeding facility that ships thousands of beagles annually to researchers was cited for dozens of alleged violations of the Animal Welfare Act in reports published last week. . . . “The depth and scope of this suffering is almost beyond words. These conditions did not spring up overnight and reveal a callous indifference to even the most basic precepts of animal welfare,” says Eric Kleiman, a researcher with the Animal Welfare Institute who has monitored inspection reports for decades and who reviewed the Envigo reports for ScienceInsider. Kleiman says he has never seen so many serious citations result from a single inspection at a single facility. “It’s really extraordinary.”

Envigo, a leading supplier of research animals, pleaded guilty yesterday to criminally violating the U.S. Animal Welfare Act (AWA) by neglecting thousands of beagles at its Cumberland, Virginia, breeding facility. The resulting overcrowding, filth, untreated disease, and hundreds of unexplained puppy deaths generated national headlines and a high-profile rescue operation in summer 2022, when the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) seized 4000 dogs that were eventually adopted. . . . “For the first time in history, a research supplier has pled guilty to the crime of conspiring to violate the Animal Welfare Act and is paying an unprecedented fine,” says Eric Kleiman, an independent animal protection researcher. “That’s some measure of accountability for the untold numbers of beagles who needlessly suffered and died.”. . .Kleiman took to task USDA, which is responsible for monitoring and enforcing compliance with the AWA. Although USDA issued the facility more than 60 citations in July 2021 and May 2022, it took no enforcement action and allowed the facility to keep operating. “Envigo’s abhorrent record should have resulted in permanent USDA license revocation. That’s the fault of USDA leadership, which the Department of Justice … commendably bypassed to save thousands of beagles,” Kleiman said.

Daniel J. Moulton—A Slow Motion Train Wreck Enabled by USDA and Researchers who Continued to Purchase Chinchillas

For years, Moulton had the most “direct”—the most severe type of critical citation—out of over 11,000 entities regulated under the AWA. APHIS never confiscated a single chinchilla, despite documenting what USDA lawyers would call “immense, avoidable” suffering of untold numbers of chinchillas for over a decade. Despite this abhorrent record, researchers continued to purchase chinchillas from Moulton.

A rare court hearing later this month—the first in 6 years involving a research-related animal facility—could strip the license of one of U.S. scientists’ only suppliers of chinchillas because of animal welfare violations. The docile South American rodents, which have ears similar to humans, are a key model for hearing studies. . . . The USDA complaint that prompted the hearing alleges that Moulton’s facility, which holds about 750 animals, is filthy and fly-infested, with exposed nails and sharp wire points protruding inside cages, undiscovered dead animals, and scores of sick and unhealthy chinchillas that do not receive adequate veterinary care. The complaint cites evidence from 3 years of USDA inspections ending in 2017, which noted chinchillas with weeping wounds and sores, untreated abscesses, and crusted, discharging eyes. Since 2014 USDA has cited Moulton 112 times for alleged AWA violations, most recently after an inspection in May. By comparison, 11 USDA-regulated facilities that supply another small mammal—rabbits—for research have together incurred a total of 35 citations since 2014, an average of 3.2 per facility. “This is the worst

animal care record I have ever seen in terms of its severity and its long-term nature,” says Eric Kleiman, a researcher at the Animal Welfare Institute who has been tracking AWA enforcement for 30 years. The last research-related animal facility to confront a USDA judicial hearing was Santa Cruz Biotechnology in 2015. That company, which housed goats and rabbits used to make antibodies, agreed to a settlement that included a $3.5 million fine and the loss of its USDA licenses. . . . Researchers use chinchillas for studies of hearing loss and of ear infections and their treatment. In 2019, U.S. scientists used 1250 of the animals, according to USDA data. Since 2010, National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded researchers have published 177 papers indexed in PubMed that use chinchillas; of the minority that identify an animal supplier, several name Moulton. MCR remains the only chinchilla supplier listed in the Laboratory Animal Science Buyers Guide published by the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science (AALAS). As part of its fee-based advertising, AALAS also features Moulton in its Vendor Showcase on the website of its buyers guide….NIH-funded researchers continue to use Moulton chinchillas, such as a group at the University of Nevada, Reno, School of Medicine that published this preprint in May.

In the United States, Moulton Chinchilla Ranch, in Minnesota, seems to be the only company that breeds and sells chinchillas for medical research. But after being cited for more than a hundred alleged animal welfare violations between 2013 and 2017, owner Daniel Moulton is in court this week fighting to keep his operating license. . . . This is the first federal animal welfare case involving research animals to go before a judge in six years, says Eric Kleiman, a researcher at the nonprofit Animal Welfare Institute. . . . This chinchilla proceeding is “a case study of everything that is wrong with the animal welfare system, he says. According to Kleiman, the business should have been shut down and its animals seized years ago.

At a U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) administrative hearing that concluded on October 8, Judge Jill Clifton revoked Moulton’s license to breed chinchillas and issued $18,000 in penalties in an oral decision. She said that the welfare violations at Moulton Chinchilla Ranch were part of an overall pattern of chronic problems with the animals’ health, sanitation, and safety….The hearing lasted 18 days and was the first animal welfare case involving research animals to go before a judge in six years, according to Eric Kleiman, a researcher at the nonprofit Animal Welfare Institute. . . . “Like so much of what the USDA does,” Kleiman says, the judge’s suspension now, years after the violations began, is “too little, too late.”

USDA’s Lack of Transparency

In February 2017, APHIS caused a firestorm when it abruptly removed inspection reports and enforcement actions from its website. APHIS’s rationale for the removal, and Eric’s ongoing analysis regarding its effects, were covered in the Washington Post, Science, and others. Congress eventually forced the agency to restore the records by amending the Animal Welfare Act, with over 200 Representatives and Senators citing the plunge in inspection report citations as one of their reasons.

But it's difficult for the public to know whether the company [Thomas D. Morris Inc.]—which supplied animals used in at least 48 biomedical studies published since 2012—has kept a clean record. That's because, on 3 February, USDA abruptly removed inspection reports, warning letters, and other documents on nearly 8000 animal facilities that the agency regulates, including Thomas D. Morris, from public databases. . . . USDA officials said the removal was prompted by their commitment to “maintaining the privacy rights of individuals” identified in the documents, which animal rights groups, journalists, and others have regularly used to publicize the failings of AWA violators. And they say they are still reviewing the withdrawn documents, with an eye toward blacking out information that shouldn't be public before reposting them. So far, APHIS has reposted inspection reports on most of the 983 research facilities that it regulates. But according to a 19 May analysis by the Animal Welfare Institute in Washington, D.C., it has not restored records covering 94% of the 3333 breeders and dealers that provide animals for the pet trade and, in some cases, research. “Are huge companies [that supply research animals] like Marshall Farms, Covance, Charles River online? Yes. The rest are not because they are licensed as individuals. This has chilling ramifications,” says Eric Kleiman, who conducted the analysis for the Animal Welfare Institute.

The Donald Trump administration appears to have reversed its decision to remove from public sight the results of past government inspections of animal research facilities. But getting hold of new inspection reports is proving to be another matter. An animal welfare researcher has found that only four reports have been posted during the first quarter of 2017…The data on new inspections were provided to ScienceInsider by Eric Kleiman, a researcher with the Animal Welfare Institute in Washington, D.C. He reviewed the more than 7000 pages of inspection reports for research facilities in 49 states and the District of Columbia that are currently available in the APHIS database. (Data for Oklahoma are missing; they are still being reviewed, according to USDA.). . . . Kleiman believes that the “vast majority” of past inspection reports have been restored, based on his analysis of the currently listed research facilities, compared with a list of registered research facilities that he downloaded from the agency website last fall, before the data were scrubbed. But that does not satisfy him. "Why post the inspections online at all if they are going to remain static, like dinosaurs in the tar pits?" he asks. “This is misleading, pure and simple.” Kleiman also takes issues with USDA's explanation in February that it was scrubbing data from the website in part “based on our commitment to being transparent.” The new policy, he says, is “the opposite of ‘transparent.’”

USDA removed animal welfare reports from its site. A showhorse lawsuit may be why.

-The Washington Post

The records removal has prompted broad outcry from animal protection groups, some of which characterized it as an assault on transparency by the Trump administration. Industries regulated by the USDA, including groups representing zoos and research labs, have also been critical. . . . The USDA last posted enforcement records in August, according to Eric Kleiman, a researcher at the Animal Welfare Institute who shared information about the lawsuit with The Washington Post. . . . Some involved SNBL, a Washington state based company that imports primates for research. In September, the USDA filed a complaint accusing the company of violations associated with the deaths — including by thirst and strangulation — of 38 monkeys imported from Asia. Kleiman obtained the unredacted complaint through a FOIA request, and it was published on the websites of the Seattle Times and the Animal Welfare Institute. But in November, Kleiman noted, the USDA filed a motion to seal its own complaint. It sought to redact information about SNBL’s nearly $10 million profit over two years, as well as the number of monkeys it imported and used annually — the kind of information not covered under FOIA exemptions.

Advocates at the nonprofit Animal Welfare Institute say the division of the USDA tasked with enforcing laws against animal cruelty in research is limiting transparency in the complaints it files, making it difficult for watchdog groups to keep tabs on alleged offenders. The Washington, D.C.-based group says the USDA recently filed a request to redact portions of its own September 2016 complaint against SNBL, a company that imports monkeys to facilities in Alice, Texas and Everett, Washington, and which the USDA alleges has been negligent in allowing the gruesome deaths of 38 of the animals since 2010. While the disturbing descriptions of the monkeys' deaths — which include thirst, suffocation and strangulation — remain intact, USDA curiously asked for the original complaint to be sealed and replaced with a copy that redacts the company's financial information, the number of animals it imported. . . . Much of the redacted information is publicly available elsewhere, including the USDA's own online database. It's a puzzling move, since the Animal Welfare Institute had already received a copy of the original complaint from the USDA's Freedom of Information Act office, which did not redact anything. . . . The unredacted complaint reported that SNBL grossed nearly $10 million and sold more than 2,800 animals between 2014 and 2015. Nearly 6,000 animals were used in research over that same time. The company was previously fined for violations of the Animal Welfare Act in 2008 and 2009, for which it paid a whopping $13,803.

The US Department of Agriculture provoked a storm of criticism in February when it removed an entire database documenting its enforcement of animal welfare laws from the web. On Friday, in response to a Freedom of Information Act request from BuzzFeed News, the agency released the first batch of documents related to its decision to hide the material from public view. The contents: 1,771 completely blacked-out pages, redacted in their entirety. “They've been the opposite of transparent regarding this whole issue,” Eric Kleiman, a researcher with the Animal Welfare Institute, an advocacy group based in Washington, DC, told BuzzFeed News. “There have been no explanations, no anything. And this just continues it.” On Feb. 7, facing a chorus of protest that had united animal welfare groups with scientists involved in experiments using animals, the USDA explained that the decision to remove the material was triggered by an ongoing lawsuit. . . . Compared to before the sudden February takedown, animal welfare groups say that it’s now much harder to hold the USDA to account in its prosecution of institutions that violate animal welfare laws.“We really kept an eye on the enforcement actions, and they’re still not up,” Kleiman said.

Animal Abuse at USDA’s Own Labs

After the New York Times broke the story about animal abuse at the USDA-owned Meat Animal Research Center in Nebraska, Eric conducted an analysis of other labs within the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service. USDA’s failure to enforce the AWA included its own research labs.

A local U.S. Department of Agriculture research facility was recently cited for inadequate veterinary care and improper handling of animals resulting in the overheating death of 32 quail chicks after a wide-ranging federal effort to improve animal welfare at federally-funded research facilities. . . . A USDA official said it is within the realm of possibility that corrective measures were completed in the two days between the APHIS and IACUC inspections, but Eric Kleiman, a researcher at the D.C.-based nonprofit Animal Welfare Institute, said the two inspections are contradictory. “That’s exactly what they were cited for two days prior,” Kleiman, said. “And it’s checked like everything is hunky dory.” After all of the internal ARS actions to improve animal welfare at their facilities, including establishing committees and walking research facility employees through pre-compliance reviews to help them pass inspections, Kleiman said it’s unfortunate that so many ARS facilities still failed to pass their inspections. “This, again, is after all this publicity … after the USDA walks them through how to pass an inspection,” Kleiman said. “This still happens; this is the first time that any of these facilities have ever had even a semblance of an independent oversight review.” He said there is a larger issue at play. Less than month after the New York Times story on the Meat Animal Research Center, Oregon Rep. Earl Blumenauer introduced the Animal Welfare in Agricultural Research Endeavors Act, or AWARE Act, to include farm animals in federal research labs in the Animal Welfare Act. A vote was never held. Without the AWARE Act, Kleiman said the USDA has no authority to enforce the citations that APHIS issued in their inspection reports. “There is no enforcement mechanism for the Poisonous Plant Research Laboratory or for any of the other 36 agricultural research service labs,” Kleiman said.